Let’s be honest for a second. Writing. That skill we know our students desperately need… and the one that somehow never quite fits into a lesson. Sound familiar? You look at the clock, look at the syllabus, and think: “I should do some writing today…” And then—boom! Time’s gone.

And when we do try to squeeze writing into class, it feels… weird. Students are working individually, heads down, writing quietly. Necessary? Absolutely. But also a bit lonely. A bit silent. And if you’re anything like me, there’s that feeling that you’re “not really teaching” because you’re not actively doing something every second. Asking them to write at home? Yeah… no. We all know how that story ends.

So here’s the challenge: how do we give them real writing practice, keep it guided, make it engaging, and still protect the process? Tricky? Yes. Impossible? Not at all. I’ve used the small whiteboards on my classroom walls (but big sheets of paper do the job too) and the results were much better than I expected. Let me show you how it works.

Step 1: Setting the model (with a little help from AI)

First things first. I used AI to help me build the presentation that introduces the writing task. Nothing fancy, no complex prompt engineering. I literally typed: “How to write an opinion essay with examples.” That’s it.

What matters here is the transparency of the process. I want students to see that AI can act as a support tool, not a shortcut. From one simple prompt, the tool generated a clear structure, key language, and examples that we could then analyse, discuss, and question together. Below, you’ll see exactly what that prompt produced.

Should you need this same presentation with AI voiceover, click here.

Note: Click on the three dots to view the presentation full screen.

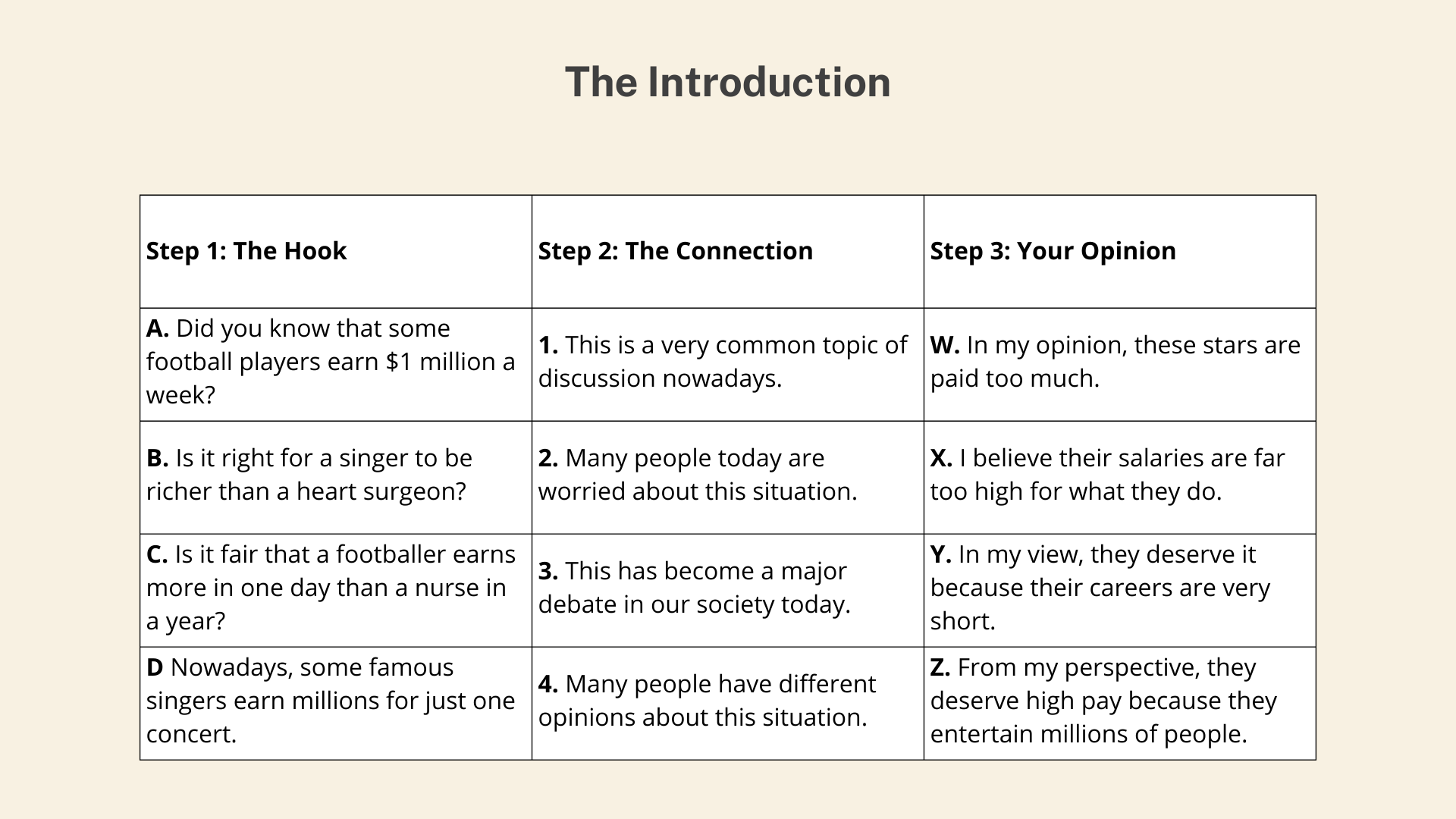

Teaching how to write a strong introduction

Before students can write anything, they need something to react to. A topic. A bit of controversy. Something that makes them think, “Hmm… do I agree with that?” So we start with a clear statement and, just as important, the freedom to choose a side,

STARS AND FOOTBALLERS ARE PAID TOO MUCH MONEY

When writing an opinion essay, you can completely agree, completely disagree, partially agree or partially disagree. The important thing is that your position is clearly stated and that the points you make in the topic sentences of the main part fully support the position you have taken.

Once they have decided whether they agree or disagree, we zoom in on one specific skill: the introduction. Not a full essay. Not paragraphs and paragraphs. Just the opening. To make it manageable, I introduce the 3-Sentence Formula. Simple, structured, and very student-friendly.

A good introduction only needs three things:

- The Hook – a short question or a striking fact (big numbers work wonders here).

- The Connection – a sentence that shows this is something people talk about.

- The Opinion – a clear statement of what you think.

To practise this, students don’t write from scratch straight away. Instead, they build an introduction by choosing one option from each column: a hook, a connection, and an opinion

At this stage, the goal isn’t originality—it’s control of structure. Once they understand how a solid introduction is built, we can slowly remove the scaffolding and let them write with more freedom.

Brainstorming 3 ideas that support their position

Now that they’ve clearly decided their position, it’s time to brainstorm ideas. I give them one simple task: write three ideas that support your opinion about the statement. These ideas will later become the body paragraphs. We won’t necessarily use all three, but thinking of an extra one gives them options and makes them feel more secure.

- Idea 1 (footballers earn more than essential workers/they generate huge income and entertainment)

- Idea 2 ____

- Idea 3____

Grouping students

By now, students have written their own individual introductions. That step matters—everyone has a clear opinion. Now I put them into pairs or groups of three, but not randomly. I group them by opinion: agree with agree, disagree with disagree. Otherwise, it doesn’t work. Once grouped, they move to the whiteboards, and we’re ready to build the body paragraphs.

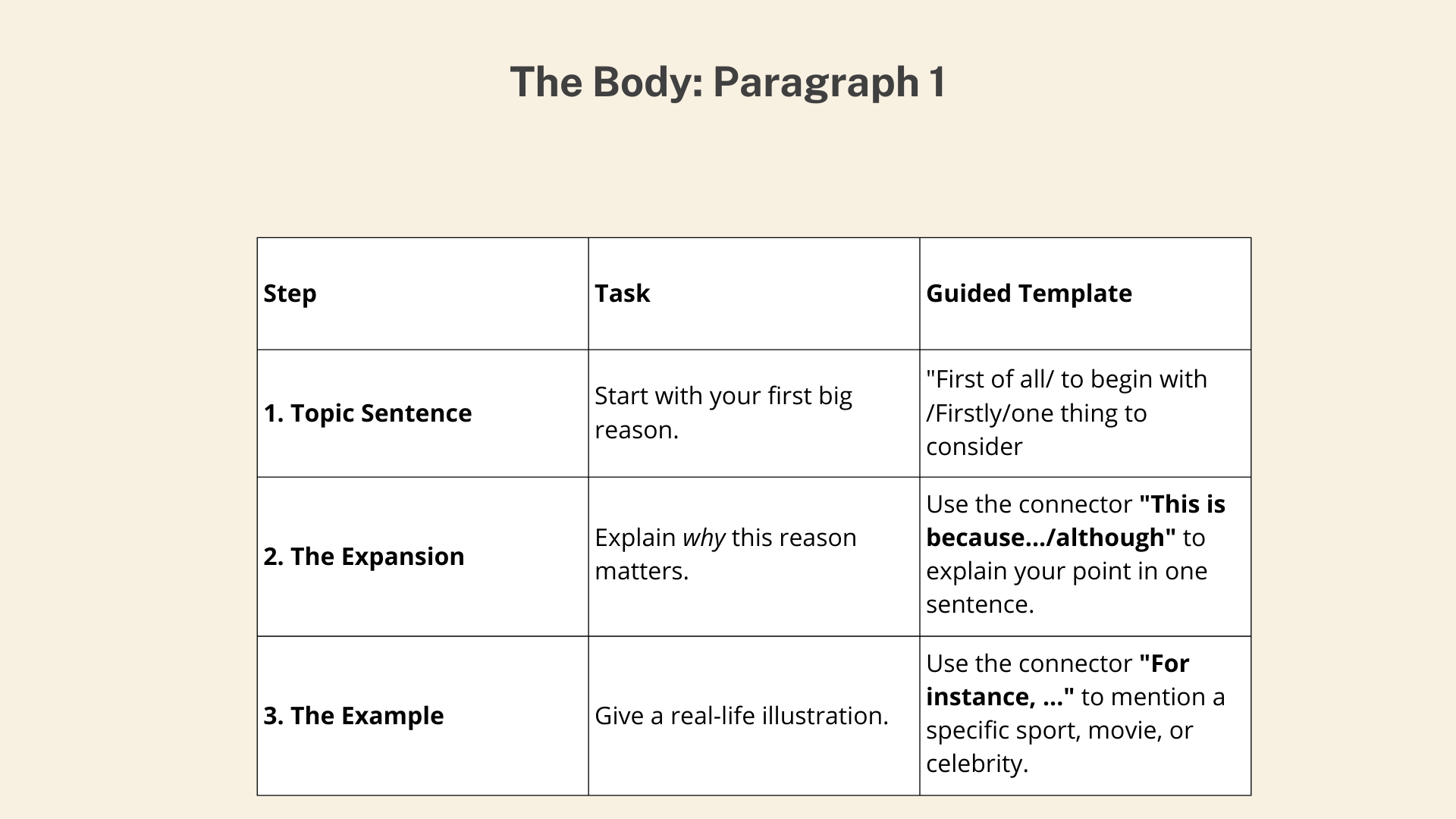

The body of the essay

And again, we go step by step. No full essay at once. No panic.

I remind them of one key rule: One main idea per paragraph. You explain it, you add an example, and you move on. New idea? New paragraph.

To keep things guided, I don’t show everything at once. I first present the structure of the first body paragraph. Students choose the connectors they want to use, discuss which one fits best, and complete the paragraph on their whiteboard. Only when that first paragraph is finished do I reveal the second box with the next idea.

Body Paragraph 1: The Main Argument

Goal: Introduce the first reason why you hold your opinion and provide a specific example.

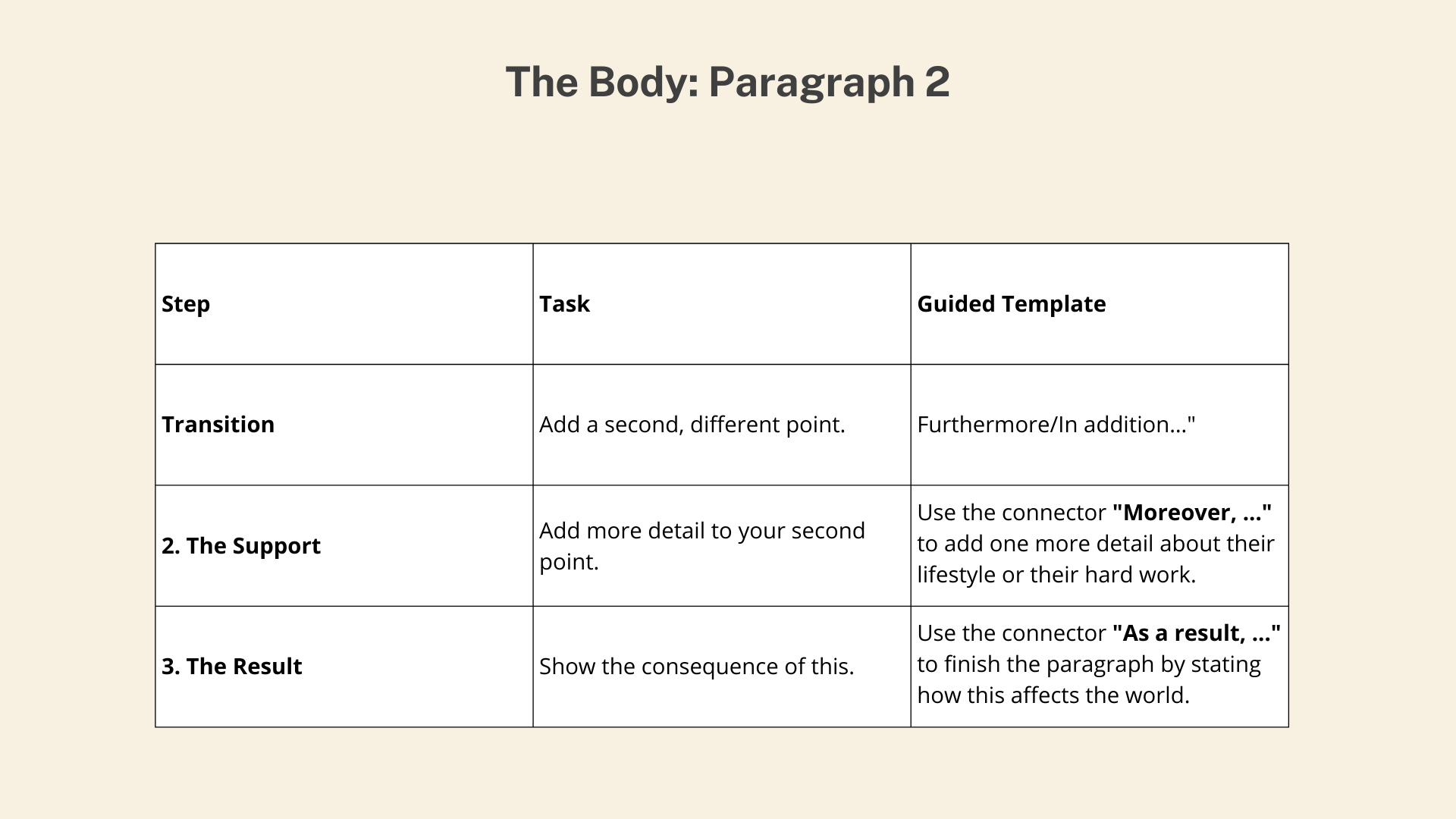

Body Paragraph 2: Adding Detail

Goal: Provide a second reason and look at the “human” side of the issue (the effort or the impact on society).

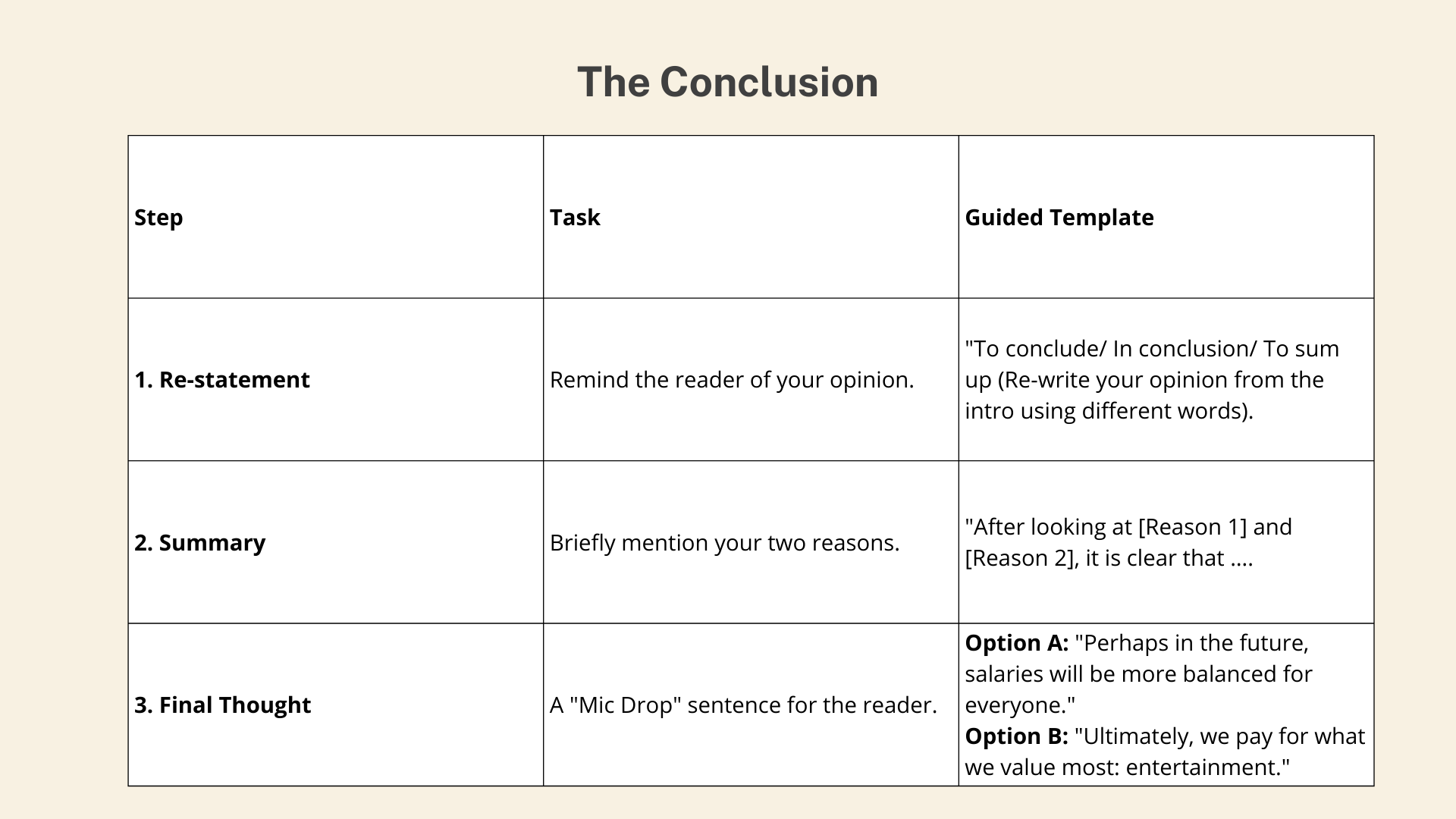

Time for the conclusion: closing the essay properly

Now it’s time to wrap things up—the conclusion. Before they write, I quickly remind them what a good conclusion does. No new ideas here.

A strong conclusion is simple and clear:

-

Restate your opinion using different words

-

Briefly summarise your main ideas

-

End with a final thought that sounds confident

Then I display the last box. By this point, they already know the routine, so they get straight to work.

The Conclusion: The Final Word

Goal: Summarize the main points and leave the reader with a final thought.

Final step: revising, polishing, and thinking again

Before I step in, students re-read what they’ve written. This is their moment to spot mistakes, improve wording, and polish ideas. Only after this do I give teacher feedback.

The last part is one of my favourites. Students are assigned an essay that defends the opposite opinion to their own. Agree reads disagree. Disagree reads agree. The goal isn’t to correct—it’s to understand. To see how the same topic can be argued differently. And yes… sometimes someone changes their mind.

If you’d like to try this sequence yourself, you can download the PDF with all the steps and adapt it to your classroom.

Hope it is helpful! Let me know in the comments below!